The presence of “hazardous” materials in your workplace can trigger a wide variety of environmental health and safety requirements. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and state worker protection agencies issue standards to protect workers during occupational handling and storage. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state environmental agencies issue requirements governing the management of hazardous wastes, and emissions to a variety of environmental media (air, water and land).

The presence of “hazardous” materials in your workplace can trigger a wide variety of environmental health and safety requirements. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and state worker protection agencies issue standards to protect workers during occupational handling and storage. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state environmental agencies issue requirements governing the management of hazardous wastes, and emissions to a variety of environmental media (air, water and land).

But what happens when your workers themselves become contaminated? Some OSHA standards address predictable routine exposures by requiring employers to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) that covers workers’ clothes and/or changing and shower areas for use at the end of each shift (e.g., HAZWOPER Standard provisions at cleanup sites) so workers leave clean. When an OSHA standard requires such sanitation facilities, they are subject to general requirements under OSHA’s Sanitation Standard. For accidental exposures, several standards require employers to provide drench showers and/or eye wash stations (e.g., Dipping and Coating Standard). If these requirements were implemented perfectly, no employee would carry any contamination out of your workplace.

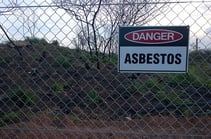

Despite these theoretical safeguards, however, there’s a long history of workers who go home “dirty” and end up exposing their families to hazardous materials, including asbestos, heavy metals and lead. These are referred to as take-home toxins. These can result in dangerous exposures to family members and other non-employees—especially in children whose growing bodies and faster metabolisms make them especially susceptible, and may also be more likely to exacerbate problems through hand-to-mouth transfers.

Are employers liable for these exposures? Take-home exposures have led to a steady trickle of “toxic tort” lawsuits by workers’ families, claiming harm from an employer’s negligence. The pace of such lawsuits has declined because compliance with OSHA and EPA rules stops more contamination inside the workplace, but some cases still occur.

Late last year, the California Supreme Court unanimously found defendant employers potentially liable for the effects of asbestos exposures during the 1970s – 40 years in the past and prior to contemporary worker protection and hygiene standards – in three cases that had been consolidated on appeal (Kesner v. Superior Court). This decision reversed longstanding precedent from state appellate courts, adding California to the list of jurisdictions that hold employers liable for offsite harm to employees’ families.

What Is the Standard for Tort Liability?

States have somewhat different standards for liability, but the California Supreme Court’s multi-step approach in Kesner is typical:

-

Duty of care, owed by the defendant to the plaintiff. Worker protection standards clearly assign employers a duty of care. But what about the employees’ (offsite) family members?

-

Breach of that duty. Was the employer negligent and/or unreasonable to allow employees to go home “dirty”?

-

Foreseeability of (harmful) impact. Was it foreseeable that the employer’s actions imposed the risk of harm to third parties, given the materials involved, and the extent of exposures?

-

Actual harm to the plaintiffs. Assuming that the plaintiff suffers a disease that might be caused by take-home toxins, but might also be caused by other exposures, is it reasonable for a jury to find the employer responsible in a substantial enough degree to impose liability?

How Does the Court Apply This Standard to Find Liability in This Case?

This case applies the tort standard as follows:

-

Duty of care. The California Civil Code applies a general standard requiring “ordinary care” in the course of business (Civil Code section 1714). The Court found that knowledge of asbestos hazards was sufficient in the 1970s that employers should have taken steps to protect workers and others – the court noted that OSHA applied that knowledge soon thereafter to create its asbestos standards (e.g., 29 CFR section 1910.1000).

-

Breach of that duty. Once the Court had applied its duty of care – retroactively – it was obvious that the employers’ failure to provide hygiene measures failed to meet that standard.

-

Foreseeability. Recognizing that a contaminated employee might expose everyone he or she encountered, the Court considered scenarios ranging from one-off exposures during movement to ongoing and potentially extensive exposures to co-habiting family members and determined that harm to members of an employee’s “household” was foreseeable.

-

Actual harm. The three cases under review all involved household members with mesothelioma, a cancer associated with asbestos exposures. Because the lower courts had decided these cases before trial, there had been no opportunity to try to prove that the victims’ cancers actually resulted from the take-home asbestos exposures. Accordingly, the Supreme Court remanded the cases for further action to decide this question.

Courts around the country have been split in these cases, over each of these elements. For example, in 2012 the Illinois Supreme Court affirmed a state appellate court decision allowing a plaintiff to argue that it was foreseeable way back in 1958-1964 that an employee’s wife might contract mesothelioma from asbestos on her husband’s dirty work clothes (Simpkins v. CSX Transportation Inc., 2012 IL 110662 (3/22/12)).

How Should My Organization Respond?

Even if you’re in a state that hasn’t found employers liable, you would be well-advised to take steps to ensure that employees go home “clean” of potentially toxic contaminants, not “dirty.” Doing so better protects the employee from the risk of harm from his or her own occupational exposure, and better protects the employee’s family from potential secondary exposures.

The following checklist can help you start to consider whether your organization’s activities pose a potential chemical threat to your coworkers’ families.

Self-Assessment Checklist

-

Does your organization use chemicals in its activities (manufacturing, construction, facilities management, etc.)?

-

Have these chemicals been assessed for their potential to harm exposed individuals, including workers?

-

Has information on Safety Data Sheets (SDSs) been reviewed, to identify potential hazards and protective measures?

-

-

Are any of these activities subject to worker protection standards administered by OSHA or other federal or state occupational safety and health agencies?

-

Hazard Communication Standard governing requiring basic protective and informational activities?

-

Air Contaminants Standard governing potential ambient exposures in workplace air?

-

Regulated Carcinogen Standard, and other standards (such as asbestos), governing exposures to chemicals that may cause cancer or other serious illnesses?

-

Standards governing exposure to materials that potentially cause immediate physical harm (flammables, reactives, etc.)?

-

Standards governing specified activities where hazardous chemicals are used (Dipping and Coating Operations Standard, Ionizing Radiation Standard, etc.)?

-

Others?

-

-

Do routine operations include work practices, administrative controls, and/or engineering controls designed to prevent worker exposures (many OSHA standards require such controls, other standards and general industrial hygiene principles encourage them)?

-

Does your workplace implement hygiene measures responsive to the potential for routine and non-routine exposures?

-

Personal protective equipment (PPE), uniforms, etc., intended to prevent exposures including contamination of employees’ street clothes?

-

Changing rooms and/or showers where employees can don/remove workplace PPE and uniforms, clean themselves at the end of their shifts and dress in their street clothes?

-

Drench showers, eye washes, other emergency equipment and post-incident hygiene and medical gear to respond to non-routine exposures?

-

-

Has your organization ever taken samples of employees’ clothing or skin at the end of shifts, to determine if any take-home toxin contamination may be underway?

Where Can I Go For More Information?

-

Kesner v. Superior Court decision

-

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Take Home Toxins webpage

Specialty Technical Publishers (STP) provides a variety of single-law and multi-law services, intended to facilitate clients’ understanding of and compliance with requirements. These include:

About the Author

Jon Elliott is President of Touchstone Environmental and has been a major contributor to STP’s product range for over 25 years. He was involved in developing 13 existing products, including Environmental Compliance: A Simplified National Guide and The Complete Guide to Environmental Law.

Mr. Elliott has a diverse educational background. In addition to his Juris Doctor (University of California, Boalt Hall School of Law, 1981), he holds a Master of Public Policy (Goldman School of Public Policy [GSPP], UC Berkeley, 1980), and a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering (Princeton University, 1977).

Mr. Elliott is active in professional and community organizations. In addition, he is a past chairman of the Board of Directors of the GSPP Alumni Association, and past member of the Executive Committee of the State Bar of California's Environmental Law Section (including past chair of its Legislative Committee).

You may contact Mr. Elliott directly at: tei@ix.netcom.com